Ghosts posed a problem for the early Church because they seemed to reflect a holdover of pagan belief and superstition. Yet reliable witnesses continued to report encounters with what to appeared to be spirits, and witnesses were not so readily dismissed as they are now.

The first place to start is with the Bible, where ghosts are scarce but not absent. The rules governing contact with the dead set the Jews apart from other religions in the ancient world, where ancestor veneration and lavish funeral rites were the norm. The spirits of the dead resided in Sheol, and were regarded as shades, using the Hebrew word repha’im. We find the word in Job 26:5, Ps. 88:10, Prov. 2:18; 9:18; 21:16, and Isa. 14:9; 26:14 referring to spirits of the dead. It is never in a positive sense: it’s used used to warn, frighten, taunt, and threaten.

This stands in contrast to pagans, where the spirits of the dead could certainly be regarded in all these ways, but also in positive ways as well. An element of ancestor worship meant these spirits were not consistently viewed as forbidden or impure. Pagans practiced “incubation”: sleeping on a grave in the hopes of receiving an oneiric (dream-state) vision of the departed with a message or prophesy. Such a practice would run afoul of Jewish purity laws, as well as prohibitions against divination.

Deuteronomy 18-9-13 is pretty emphatic on the matter of necromancy and sorcery:

“When you come into the land which the LORD your God gives you, you shall not learn to follow the abominable practices of those nations. There shall not be found among you any one who burns his son or his daughter as an offering, any one who practices divination, a soothsayer, or an augur, or a sorcerer, or a charmer, or a medium, or a wizard, or a necromancer. For whoever does these things is an abomination to the LORD; and because of these abominable practices the LORD your God is driving them out before you.”

The reason for this was very simple: it suggested man could have control over powers reserved to God alone. This forms a stark—perhaps the starkest—contrast to paganism and magic, where the visible and invisible worlds, and even the “gods” themselves, could be manipulated.

Saul: The Necromancer

Yet ghosts and references to ghosts are found in scripture and must be dealt with if we are to understand the way early Christians treated the phenomena. The most famous instance, of course, is the summoning of the spirit of Samuel by the Witch of Endor in 1 Samuel 28. (Also mentioned in 1 Chron 10:13-14 and Sirach 46:23.)

The striking thing about the Witch of Endor passage is how really diabolical it is: this is nothing less than necromancy, which is condemned by both Jews and Christians. Saul himself had prohibited the practice, which is why he meets in secret with the medium.

Saul knows he has done wrong and lost favor with God, but desires to know his fate in an upcoming battle with the Philistines. “The LORD did not answer him, either by dreams, or by Urim, or by prophets,” (1 Sam 28:6) we are told.

He disguises himself and asks the medium, “Divine for me by a spirit, and bring up for me whomever I shall name to you.” (1 Sam 28:8-9) The word used for “medium” is “ob,” which may refer either to the necromancer herself, or the object she uses to communicate with the dead, such as a skull. The text leaves out her rituals, suggesting to some that Samuel appears unbidden, thus proving to later readers that mediums have no real power. This interpretation does not appear to be supported by the text, since Samuel is annoyed at being “disturbed.”

The scene is as strange for its language as for its necromancy:

“I see a god coming up out of the earth.” [Saul] said to her, “What is his appearance?” And she said, “An old man is coming up; and he is wrapped in a robe.” And Saul knew that it was Samuel, and he bowed with his face to the ground, and did obeisance. (1 Sam 28:13–14)

The Christological interpretation would only become clear in the fullness of time, but quite obviously Samuel isn’t even a lower-case-”g” god, which is how the RSV renders “elohim.” The use of “elohim” is provocative here, but the word could also suggest a “spirit” or “divine being” as well as gods and, specifically, Yahweh.

Samuel is annoyed at being summoned from “below” (Hades), but proceeds to tell Saul that he will fall to the Philistines and that “tomorrow you and your sons shall be with me.” (1 Sam 28:19)

The appearance of Samuel challenged exegetes from ancient to medieval times. They offered a wide array of interpretations: it was the devil or a demon taking on the guise of Samuel, it was his reanimated corpse infused with spirit but not his soul (a distinction I won’t dwell on here), it was a phantasm, it was an illusion, it was actually Samuel given permission by God to appear and clothed in flesh that looked like his own, it was Samuel, who had been in Hades awaiting Christ.

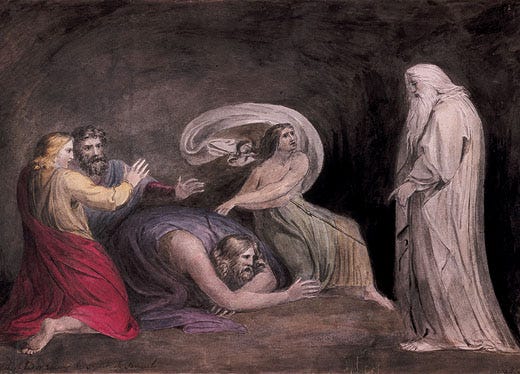

This last is suggested by Origen, who examines it at length in his Homily on 1 Kings 28. (1 Samuel is 1 Kings in some numberings.) Origen’s reading would, in time, be rejected in favor of a diabolical answer. The presence of a fairly extensive medieval art tradition for the scene shows its grip on the imagination, as medieval man came to wrestle more actively with the issue of visions, spirits, and dreams.

Next Up: Ghosts in the New Testament.

Love the use of the Blake illustration