Before we get down to St. Augustine’s thoughts on ghosts, I need to do some spadework by exploring his understanding of different ways of seeing. He explains this in On Genesis Literally Interpreted (De Genesi ad litteram), the sprawling twelve-part study that is one of his least-read major works. (Don't confuse it with the minor, earlier work, On the Literal Interpretation of Genesis: An Unfinished Book--De Genesi ad litteram imperfectus liber.) Augustine’s work follows standard ideas found in antiquity, and would prove influential with the rise of Aristotelianism in the 12th century and beyond.

Chapter 12 of De Genesi is titled “On the Heavenly Paradise: different kinds of visions,” and marks a turning point in the work in which his attention shifts from pure commentary on Genesis and related issues to a consideration of paradise.

Of particular concern here is the vision of Paul in 2 Corinthians 12:2-4, describing how he is caught up to the third heaven. The nature of this vision—and indeed, of all “dreaming and different kinds of ecstasy”—leads Augustine to identify three types of vision: corporeal, spiritual, and intellectual. To understand what he thinks of ghosts we first need to grasp these three ways of seeing.

Corporeal (visio corporalis)

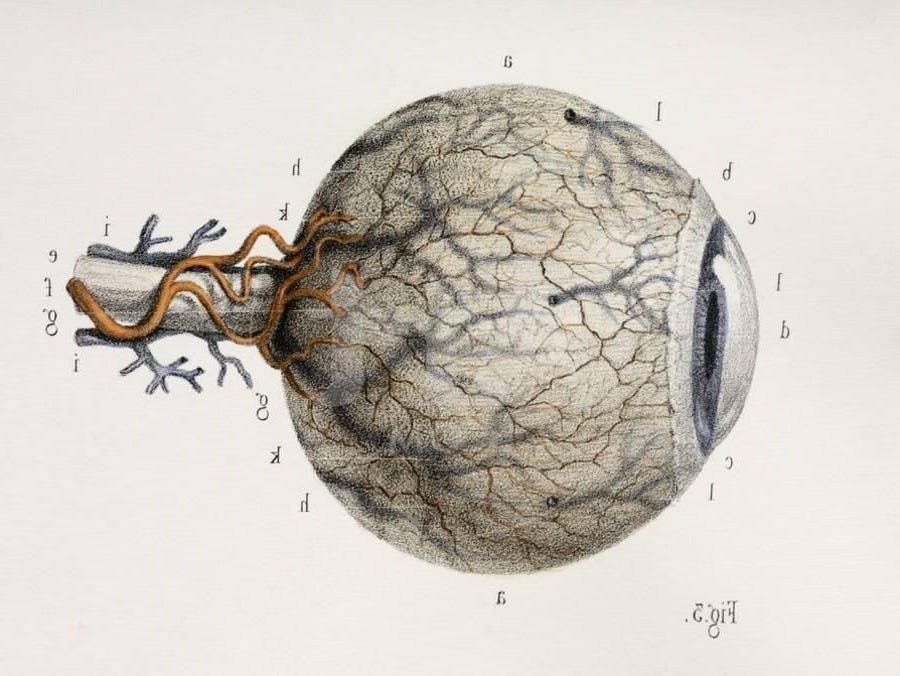

Simply stated, this is the physical sense of sight. Our idea of sight is quite different that of the ancients and medievals. We know that sight is reflected light received by the eye and transmitted to the brain through the nervous system. They had, generally speaking, two models of seeing: extromission and intromission.

Extromission suggested that a kind of beam or ray left the eye, touched the object being seen, and then returned to the eye, conveying the physical qualities (shape, size, color) of an object to the soul.

Intromission suggested that the form of object being seen emitted some element that traveled through the air (which was conceived as a medium rather than as empty space) and imprinted itself on the eyeball. Various words were used for this form, one of them being phantasma. Vision itself was thus a kind of “ghost.”

Both models suggest that a passive object has in fact an active part in being perceived by the sense of sight. This is the lowest order of vision.

Intellectual (visio intellectualis)

At the other end of the spectrum was the most exalted form of vision: the intellectual vision. This kind of vision is beyond all others: it is to see things as they really are, “not in images, but as it properly is in itself.” (De Genesi 12.15) This is a rare kind of vision, afforded only the the spiritually advanced. It begins in our intellect (mens), and seeks to contemplate God as He truly is. This is the vision of the upper part of the soul, and it is beyond any image.

Spiritual (visio spiritalis)

Between corporeal and intellectual vision, Augustine posited an intermediary way of seeing. In his “spiritual” way of seeing, neither the senses/sensus (as in corporeal) or the reason/mens (as in intellectual) are dominant, but rather the spirit of man. And he is not seeing concrete bodies, but rather semblances of bodies.

Mediating between the sensus and the mens is the imaginatio, which can receive images acquired by the eye, submit them to the judgment of the intellect, and then pass them on to the memory. It can also generate nonexistent things from the fancy of the individual. Afflictions of the body or mind could cause the spiritual vision to malfunction, creating hallucinations. "Imagination" is certainly part of this, but imaginatio goes beyond that to suggest a profound mediating role.

Augustine offers an example and explanation:

When you read, You shall love your neighbor as yourself, three kinds of vision take place; one with the eyes, when you see the actual letters; another with the human spirit, by which you think of your neighbor even though he is not there; a third with the attention of the mind, by which you understand and look at love itself.

Both corporal and spiritual vision process images, but whereas the senses produce vision in relation to a material object, the spiritual vision produces images with or without reference to a material object. The spiritual vision perceives “semblances of bodies,” either while the individual was awake or asleep. When something goes wrong in the mind or the body, those semblances may not tally with objects in the real world, and we perceive merely forms in the imagination.

In other words: ghosts.